The following fragment is taken from the book Anatoly T.Fomenko "History: Fiction or Science", vol.2. Delamere Publishing,2005.

The famous reform of the Occidental Church in the XI century by "Pope Gregory Hildebrand" as the reflection of the XII century reforms of Andronicus (Christ).

"POPE GREGORY HILDEBRAND" FROM THE XI CENTURY A.D. AS A REPLICA OF JESUS CHRIST (ANDRONICUS) FROM THE XII CENTURY. A CHRONOLOGICAL SHIFT OF 100 YEARS. THE SCALIGERITE CHRONOLOGISTS HAVE SUBSEQUENTLY MOVED THE LIFE OF CHRIST'S 1050 YEARS BACKWARDS, INTO THE I CENTURY A.D.

The great ecclesiastical reform of the XI century, conceived and initiated by the famous Pope Gregory Hildebrand, is a well-known event in the history of Western Europe and the Occidental Christian Church. It is supposed to have radically altered the life of the Europeans. As we shall demonstrate in the present chapter, the XI century "Pope Gregory Hildebrand" is really a phantom reflection of Andronicus (Christ) from the XII century A.D.

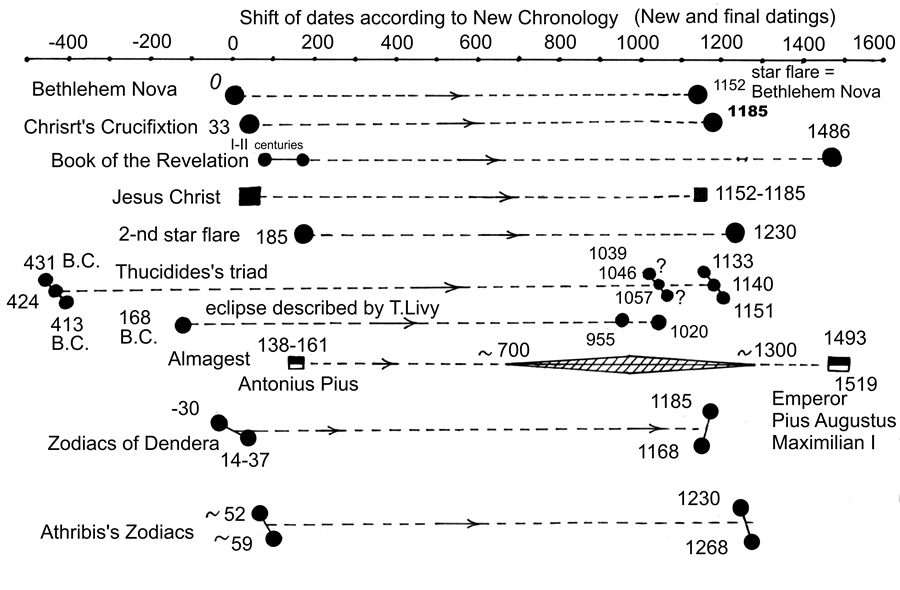

Let us explain in more detail. The decomposition of the "Scaligerian history textbook" into the sum of four shorter chronicles shifted against each other implies the existence of the erroneous mediaeval tradition that dated Christ's lifetime to the XI century A.D. This fact had initially been discovered by the author in his study of the global chronological map (the 1053-year shift that superimposes the phantom I century A.D. over the XI century A.D.). This erroneous point of view that the ancient chroniclers adhered to was further rediscovered by G. V. Nosovskiy in his analysis of the Mediaeval calculations related to the Passover and the calendar, qv in Chron6 and Annex 4 to The Biblical Russia.

One should therefore expect a phantom reflection of Jesus Christ to manifest in the "Scaligerian XI century". This prognosis is confirmed, and we shall demonstrate the facts that confirm it in the present chapter.

Our subsequent analysis of the ancient and mediaeval historical chronology demonstrated that the epoch of Christ, which is presumed to be at a distance of 2000 years from today, to have been 1100 years closer to us, falling over the XII century A.D. See our book entitled King of the Slavs for further reference. Apparently, despite the fact that the mediaeval chronologists have shifted Christ's life as reflected in the chronicles into the I century A.D., having "removed" it from the XII century, an "intermediate reflection" of Emperor Andronicus (Christ) remained in the XI century as the biography of "Pope Gregory VII Hildebrand".

This statement, which is of a purely chronological nature, is often misunderstood by religious people. This stems from the false impression that the re- dating of the Evangelical events that we offer contradicts the Christian creed. This is not so. The re-dating of the years of Christ's life that we offer taken together with the alternative datings for other events recorded in ancient and mediaeval history has got absolutely nothing to do with Christian theology.

The same can be said about the parallels between the Evangelical descriptions of Christ's life and the biography of "Pope" Gregory Hildebrand. A parallelism doesn't imply that Hildebrand's biography is based on reality and the Gospels are a myth that duplicates it. On the contrary – in our works on chronology we demonstrate our discovery that the history of the Italian Rome (where Pope Hildebrand is supposed to have been active in the XI century according to Scaligerian history) only commences from the XIV century. Also, up until the XVII century it used to differ from the consensual version substantially. Ergo, real history tells us that there could have been no Roman Pontiff by the name of Hildebrand in the XI century Italy – if only due to the non-existence of Rome itself at that epoch.

What are the origins of "Pope Hildebrand's" biography, and why does it contain duplicates of a number of Evangelical events? This issue requires a separate study. It is of great interest in itself, and remains rather contentious. In any case, if we are to assume a purely chronological stance, we shall certainly become interested in the fact that the Scaligerian history of the XI century contains a distinctive parallelism with the Evangelical events.

1.1 Astronomy in the Gospels

1.1.1 The true dating of the evangelical eclipse.

The issue of dating the evangelical events via a study of the eclipse described in the Gospels and other early Christian sources (Phlegon, Africanus, Synkellos etc) has a long history – it has been repeatedly discussed by astronomers and chronologists alike. There is controversy in what concerns whether the eclipse in question was a solar or a lunar one – we shall therefore consider both possibilities. Let us consider a lunar eclipse first. The Scaligerian chronology suggests 33 A.D. as a fitting solution – see Ginzel's astronomical canon, for instance ([1154]). However, this solution doesn't quite fit, since the lunar eclipse of 33 A.D. was all but unobservable in the Middle East. Apart from that, the eclipse's phase was minute ([1154]).

Nevertheless, the eclipse of 33 A.D. is still persistently claimed to confirm the Scaligerian dating of the Crucifixion – the alleged year 33 A.D.

N. A. Morozov suggested another solution: 24 March 368 A.D. ([544], Volume 1, page 96. However, if we are to consider the results of our research that had demonstrated the "Scaligerian History Textbook" to fall into a collation of four brief chronicles, this solution is nowhere near

recent enough to satisfy our requirements. Morozov considered the Scaligerian chronology to be basically correct in the new era; therefore, he only got to analyze the eclipses that "preceded the VIII century – that is, from the dawn of history to the second half of the Middle Ages – I decided going any further back would be futile [sic! – A. F.]" ([544], Volume 1, page 97).

We have thus extended the time interval to be searched for astronomical solutions into the epochs nearer to the present, having analyzed all the eclipses up until the XVI century A.D. It turns out that there is an eclipse that satisfies to the conditions – the one that occurred on Friday, 3 April 1075. The coordinates of the zenith point are as follows: + 10 degrees of longitude and – 8 degrees of latitude. See Oppolzer's canon, for instance ([1315]). The eclipse was observable from the entire area of Europe and the Middle East that is of interest to us. According to the ecclesiastical tradition, the Crucifixion and the eclipse were simultaneous events that took place two days before the Easter. This could not have preceded the equinox. The eclipse dating to 3 April 1075 A.D. precedes Easter (which falls on Sunday, 5 April that year) by two days, as a matter of fact. The phase of the 1075 eclipse is 4"8 – not that great. Later on, in our analysis of Gregory Hildebrand's "biography", we shall see that the eclipse of 1075 A.D. corresponds well with other important events of the XI century which may have become reflected in the Gospels.

Let us now consider the solar eclipse version. According to the Gospels and the ecclesiastical tradition ([518]), a new star flared up in the East the year the Saviour was born (Matthew 2:2, 2:7, 2:9-10), and a total eclipse of the sun followed in 31 years, in the year of the Resurrection. The Gospel according to Luke (23:45) tells us explicitly that the sun "hath darkened" during the Crucifixion. Ecclesiastical sources also make direct references to the fact of the Resurrection being accompanied by a solar eclipse, and not necessarily on Good Friday. Let us point out that an eclipse, let alone a total eclipse, is a rare event in that part of the world. Although solar eclipses occur every year, one can only observe them from the narrow track of lunar shadow on the Earth (unlike lunar eclipses that one can observe from across an entire hemisphere). The Bible scholars of the XVIII-XIX century decided to consider the eclipse to have been a lunar one, which didn't help much, since no fitting lunar eclipse could be found, either (qv above). However, since then the consensual opinion has been that the Gospels describe a lunar eclipse and not a solar one. Let us adhere to the original point of view that is reflected in the sources, namely, that the eclipse was a solar one.

We learn that such combination of rarest astronomical events as a nova explosion and a full eclipse of the sun following it by roughly 33 years did actually occur – however, in the XII century A.D. – not the first! We are referring to the famous nova explosion roughly dated to 1150 and the total eclipse of the sun of the 1 May 1185. We relate it in detail in our book King of the Slavs.

Thus, astronomical evidence testifies to the fact that the Evangelical events are most likely to have taken place in the XII century A.D. – about 1100 later than the Scaligerian "dating" ([1154]), and 800 years later than the dating suggested by N. A. Morozov ([544], Volume 1).

However, later chronologists have shifted the supernova explosion (the Evangelical star of Bethlehem) 100 year backwards, declaring it to have taken place in 1054. What are the origins of this version? It is possible that the desperate attempts of the mediaeval chronologists to find a "fitting" eclipse in the XI century played some part here. A total eclipse of the sun took place on the 16 February 1086, on Monday ([1154). The shadow track from this eclipse covered Italy and Byzantium. According to Ginzel's astronomical canon ([1154]), the eclipse had the following characteristics: the coordinates of the beginning of the shadow track are – 76 degrees of longitude and + 14 degrees of latitude (these values are – 14 longitude and + 22 latitude for the track's middle, and + 47 longitude with latitude equalling + 45 degrees for its end). The eclipse was total. Having erroneously declared this eclipse to have been the one that coincided with the Crucifixion, the XIV-XV century chronologists had apparently counted 33 years (Christ's age) backwards from this date (approximately 1086 A.D.), dating the Nativity to the middle of the XI century. They were 100 years off the mark.

Let us linger on the ecclesiastical tradition that associated the Crucifixion with a solar eclipse.

1.1.2. The Gospels apparently reflect a sufficiently advanced level of astronomical eclipse theories, which contradicts the consensual evangelical history.

The Bible scholars have long ago taken notice of the claim that the eclipse had lasted about three hours made by the authors of the Gospels. Matthew tells us the following: "Now from the sixth hour there was darkness all over the land unto the ninth hour" (Matthew 27:45).

According to Luke, "… it was about the sixth hour, and there was a darkness all over the earth until the ninth hour. And the sun was darkened…" (Luke 23:44-45)

Mark informs us that "… when the sixth hour was come, there was darkness all over the whole land until the ninth hour".

John hasn't got anything to say on the subject. The numerous commentators of the Bible have often been puzzled by the fact that the evangelists report a solar eclipse ("the sun was darkened") with its unnaturally long three-hour duration, since a regular solar eclipse is only observable for several minutes from each particular location. We consider the explanation offered by Andrei Nemoyevskiy, the author of the book Jesus the God ([576]) a while ago to make perfect sense. He wrote that "we know that a solar eclipse could not have lasted for three hours and covered the entire country [it is usually assumed that the country in question is the rather small area around Jerusalem – A. F.]. Its maximal duration could not possibly exceed 4-8 minutes. The evangelists

apparently were well familiar with astronomy and could not have uttered any such nonsense … Luke (XXIII, 44) … Mark (XV, 33) … and Matthew (XXVII, 45) … tell us that "there was darkness all over the land", which really could have lasted for several hours. The duration of the entire solar eclipse that occurred on 6 May 1883 equalled 5 hours and 5 minutes; however, the full eclipse lasted for 3 hours and 5 minutes – exactly the time interval specified in the Gospels" ([576], page 23).

In other words, the three hours specified by the evangelists referred to the entire duration of the lunar shadow's movement across the surface of the Earth and not the time a single observation point was obscured – that is, the duration of the eclipse from the moment of its beginning (in Britain, for instance) and until its end in some place like Iran. It took the lunar shadow three hours to cover the entire track that ran "all over the land", inside which "there was darkness". The phrase "all over the land" was thus used deliberately.

Naturally, such interpretation of the Gospels implies a sufficiently advanced level of their authors' understanding of the eclipses and their nature. However, if the events in question took place in the XII century and were recorded and edited in the XII- XIV century the earliest, possibly a lot later, there is hardly any wonder here. Mediaeval astronomers already understood the mechanism of solar eclipses well enough, as well as the fact that the lunar shadow slides across the surface of the Earth ("all over the land") for several hours.

Let us point out that this high a level of astronomical knowledge from the part of the evangelists is an absolute impossibility in the reality tunnel of the Scaligerian chronology. We are told that the evangelists were lay astronomers at best, and neither possessed nor used any special knowledge of astronomy.

We shall consider the issue of the "Passover eclipse" that occurred during the Crucifixion once again. Many old ecclesiastical sources insist the eclipse to have been a solar one. This obviously contradicts the Gospels claiming that the Jesus Christ was crucified around the time of the Passover, which also implies a full moon. Now, it is common knowledge that no solar eclipse can occur when the moon is full, since the sun and the moon face opposite sides of the Earth. The sun is located "behind the back" of the terrestrial observer, which is the reason why the latter sees the entire sunlit part of the moon – a full moon, that is.

All of the above notwithstanding, we have dis- covered a total eclipse of the sun that took place on 1 May 1185 falling precisely on the year of the Crucifixion, qv in the King of the Slavs. Let us remind the reader that a full solar eclipse is an exceptionally rare event for this particular geographical area.

Centuries may pass between two solar eclipses observed from this region. Therefore, the eclipse of 1185 could have been eventually linked to the moment of the Crucifixion. Hence the concept of

the "Passover eclipse". This shouldn't surprise us since in the Middle Ages a clear understanding of how the locations of celestial bodies were related to one another had been a great rarity, even for scientists.

In fig. 2.1 we can see an ancient miniature of the Crucifixion taken from the famous Rhemish Missal. At the bottom of the miniature we see a solar eclipse that accompanies the Crucifixion (fig. 2.2). Modern commentary runs as follows: "the third scene in the bottom field depicts the apocryphal scene of the eclipse observed by Dionysius Areopagites and Apollophanes from Heliopolis" ([1485], page 54. We see the Sun is completely covered by the dark lunar disc, with the corona visible underneath. The sky is painted dark, since "there was darkness all over thewhole land". Numerous spectators look at the sky in fear, whilst the two sages point their fingers at the eclipse and the Crucifixion depicted at the top of the picture.

In fig. 2.3 we see the fragment of a New Testament frontispiece from La Bible historiale,a book by Guiart des Moulins ([1485], ill. 91). We see the Crucifixion accompanied by a total eclipse of the sun; we actually see a sequence of two events in the same miniature – on the left of the cross there is the sun that is still shining bright, while on the right it is completely obscured by the blackness of the lunar disc. This method was often used by mediaeval artists for a more comprehensive visual representation of sequences of events – "proto-animation" of sorts.

Yet another miniature where we see the Crucifixion accompanied by a solar eclipse can be seen in fig. 2.4 – it allegedly dates to the end of the XV century ([1485], ill. 209). We see two events in a sequence once again. The sun is still bright to the left of the cross, and it is beginning to darken on the right where we see it obscured by the moon, which is about to hide the luminary from sight completely. We see a starlit sky, and that is something that only happens during a total eclipse of the sun.

It is interesting that the traces of references to Christ in mediaeval chronicles relating the XI century events have even reached our day. For instance, the 1680 Chronograph ([940]) informs us that Pope Leo IX (1049-1054) was visited by Christ himself: "It is said that Christ had visited him [Leo IX] in his abode of repose, disguised as a beggar" ([940], sheet 287). It is important that there are no similar references anywhere else in the Chronograph ([940]) except for the renditions of the Gospels. In the next section we shall discover evangelical parallels in the biography of Pope Gregory VII, who had died in 1085. It is possible that Gregory VII is a reflection of Jesus Christ, or Emperor Andronicus, stemming from the fact that the Romean history of Constantinople was relocated to Italy (on paper only, naturally).

This is why the first "A.D." year mentioned in a number of chronicles could have erroneously referred to 1054 A.D. This eventually gave birth to another chronological shift of 1053 years. In other words, some of the mediaeval chronologers were apparently accustomed to dating the Nativity to either 1054 or 1053 (instead of 1153, which is the correct dating).

A propos, the beginning of the first crusade – the one that had the "liberation of the Holy Sepulchre" as its objective – is erroneously dated to 1096 ([76]) instead of circa 1196. On the other hand, one should pay attention to the mediaeval ecclesiastical sources, such as The Tale of the Saviour's Passions and Pilate's Letter to Tiberius. They often relate the events involving Christ in greater detail than the Gospels. And so, according to these sources, Pilate had been summoned to Rome immediately after the Resurrection and executed there, and the Caesar's troops marched towards Jerusalem and captured the city. Nowadays all of this mediaeval information is supposed to be of a fantastic nature, since no Roman campaign against Jerusalem that took place in the third decade of the first century A.D. is recorded anywhere in the Scaligerian history. However, if we are to date the Resurrection to the end of the XII century, this statement found in mediaeval sources immediately assumes a literal meaning, being a reference to the crusades of the late XII – early XIII century, and particularly the so-called Fourth Crusade of 1204, which resulted in the fall of Czar-Grad.

Later chronologists, confused by the centenarian chronological shift, have moved the dates of the crusades of the late XII – early XIII century to the end of the XI century. This resulted in the phantom crusade of 1096, for instance, which is presumed to have resulted in the fall of Jerusalem ([76]).

1.2. The Roman John Crescentius of the alleged X century A.D. as a reflection of the Evangelical John the Baptist from the XII century A.D. A biographical parallelism

As we demonstrate in our book King of the Slavs, John the Baptist had lived in the XII century A.D. In the present section we shall discuss the correlation between his two phantom reflections in the I and the X century A.D.

The chronicles that tell us about the origins of the Second Roman Empire dating from the alleged I century A.D. include a detailed description of the great ecclesial reform implemented by Jesus Christ and partially instigated by his precursor John the Baptist. This is what the Gospels tell us. As one can see in Chapter 6 of Chron1, most of these events can be linked to the dawn of the X-XIII century Roman Empire – namely, the XII century A.D. One has to bear in mind that these events took place in the New Rome, or Czar-Grad on the Bosporus. The identification of the Second Empire as that of the X-XIII century is a consequence of the chronological shift of roughly 1053 years. It can be represented as the formula P = T + 1053, where T is the Scaligerian B.C. or A.D. dating of the event, and P – the new one suggested by our conception. Thus, if T equals zero (being the first year of the new era), the P date becomes equal to 1053 A.D. In other words, the results related in Chapter 6 of Chron1 formally imply the existence of a mediaeval tradition dating the beginning of the new to 1053 A.D. in modern chronology.

Thus, the initial dating of Christ's lifetime to the XI century made by the mediaeval chronologists was 100 years off the mark. The real date of the Nativity falls on 1152, qv in our book entitled King of the Slavs.

We have observed the effects of the chronological shift (P = T + 1053) on the millenarian Roman history. If we are to move forwards in time along this parallelism, we shall eventually reach the "beginning of the new era". What discoveries await us here? The answer is given below in numerous biographical collations and identifications. The "a" points of our table as presented below contain numerous references to the book of F. Gregorovius ([196], Volume 3).

In our relation of the parallelism we shall concentrate on its "mediaeval half ", since the content of the Gospels is known to most readers quite well, unlike the mediaeval version. From the point of view of the parallelism that we have discovered, the mediaeval version is important as yet another rendition of the evangelical events. One should also bear in mind that nowadays the events related to Crescentius and Hildebrand are supposed to have happened in the Italian Rome. This is most probably untrue. The events described in the Gospels had taken place in Czar-Grad on the Bosporus, and were subsequently transferred to Italy on paper when the Italian Rome emerged as the new capital in the XIV century A.D. This young city had been in dire need of an "ancient history", which was promptly created.